Born in 1925, raised in Airmont, schooled in Bluemont, and now a resident of Berryville, Roberta Underwood has a gift for storytelling. In her December 1, 2011 interview, she talked about her early life on her parent’s farm, artistic and literary neighbors, a life as a teenager in the war years, and the independent-minded community which started the Bluemont Fair.

![]()

“Up On the Mountain:” Ball Alley and John Fox

Susan Falknor. I understand that you grew up in Airmont, just a few miles down Snickersville Turnpike from Bluemont. What was it like then? Was it the same as it is now?

Roberta Underwood. Well there’s just a few more houses now. It was mostly farmland then. They’ve built several houses but it is not as built up as some of the other areas.

S. When did you parents buy that farm?

R. It was 1922. I was born three years later, in 1925.

S. So they moved down off the mountain, right?

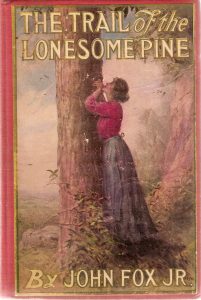

R. Yes. Before they lived up there on Ball Alley. Do you know where Ball Alley is? It was at that time, a huge tract of land on 601, 3 miles south of Route 7. It was owned by Dr. Ammiee Moore. Now it has been cut into smaller parcels. His wife was a sister to John Fox. He wrote The Trail of the Lonesome Pine. [A 1909 novel, a 1913 popular song, and 1936 movie.]

S. Well, I have heard of the book, Trail of the Lonesome Pine, but….

R. [Laughs.]It was compulsory reading when I went to school. It was written in the Southern part of Virginia, but he lived up on the mountain with his sister. My parent’s house was in Clarke County, and their house was on the other side of the road, which was Loudoun County. I think Roger Cline owns the place now. About 15 years ago, one of my sisters had come up, because she had lived on the mountain back then and wanted to see how authentic his cabin still was.

R. [Laughs.]It was compulsory reading when I went to school. It was written in the Southern part of Virginia, but he lived up on the mountain with his sister. My parent’s house was in Clarke County, and their house was on the other side of the road, which was Loudoun County. I think Roger Cline owns the place now. About 15 years ago, one of my sisters had come up, because she had lived on the mountain back then and wanted to see how authentic his cabin still was.

This cabin, it had a bed and it had a chair and it had a heating stove. And that was just about it. The chair was a rocking chair.

Mr. Fox had lived there, but he came to the house and took his meals. My mother cooked for him. See, the Moore’s cook had gone to Washington for the winter. One thing, my daddy was rather perturbed about was Mr. Fox wanted his plate warmed. Of course, he just meant putting it up in the warming closet, on the old cook stove?

S. I do.

R. Just put it in there and take it out before he ate his meal.

S. So he came here to have time to write, privacy, quiet…. And your mother made it possible by furnishing meals.

R. Right. His sister and of course his brother-in-law stayed in Washington because he was a physician. Ammie Moore. Like a lot of people in that day they had homes on the mountain in the summertime and then they would go back to the city. The cook’s name was Mary, I’ve heard Mother talk about her. Of course, she went back home with them. So they just closed the house up. He stayed in this cabin. And Mother cooked for him and served him off this warm plate.

S. (laughs) And your father felt like that was like spoiling Mr. Fox…

R. Right. Well you see, he didn’t get that much attention himself. Maybe a little jealousy there. (laughs)

Her Parents’ Journey – from Elopment to a Golden Wedding

S. What was your mother’s name?

R. Lula McCarty. Lula Martz McCarty, because she was a Martz-McCarty.

S. And what was your father’s name?

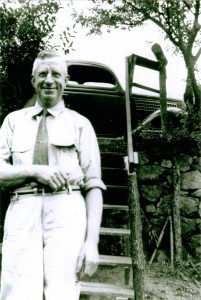

R. William. Will. This photo was taken at the house at Airmont. This is the old house. See what happened is that Papa had sold the farm in 1959, but he asked if he could stay there—I don’t know—two or three months because he wanted to have his anniversary in the old house. That was a big deal. My goodness, we had people from Timbucktoo. A lot of fun.

S. So they moved there in the 1920s. And how many acres did they have?

R. The original was 104 acres, and then he bought what we called the Kemp Field—Aunt Hattie’s place [Airwell]. That land went clear up to the Black church on Airmont Road and beyond. And that’s where they put their second house. It was, I don’t know, probably 15 acres in the Kemp Field plus 5-6-7 acres. It ended up being about a 125-acre farm. It was a wooded area. There are houses there now.

The stone fence—Papa laid that. He was not a stone mason, but he did that.

We only had two fields that were not fronted. Look when you come to Gordon’s house. What we called the bottom and the backfield. Everything else was frontage on a road: 734 or 719. It was valuable land. I mean, I don’t think Papa got the money, but the people who sold after him did—they sold it in sections.

He sold in 1959. That was the year they’d been married 50 years. He sold it, I want to say, in August, September, somewhere along in there. They had the party the 20th of November of that year.

They had eloped when they married. You know, when you raise children, you always got to show them your best side. And they’d been married several years, and I was quite good-sized when I found out about that my mother eloped. She ran off.

Well, finally she told us about it. She didn’t know Papa that long. And they decided to get married. It was 1909. And they were going to Hagerstown, Maryland. So she told one sister, and she helped her.

Papa came with the horse and buggy up to 601. He waited up there. And he had arranged with a family friend, a friend of her father, John Beavers (see photo right), to come down and to entertain the parents so Mother could slip off. John Beavers entertained her parents so she and Papa could elope.

Mother was upstairs and came out onto the porch roof. There was a bank and she slipped off and she got on the bank and went up the hill. Of course, she was gone before they knew anything about it. They came to Berryville in this buggy and went to Hagerstown on the train and got married.

Mother had never been out of this area at all, or out of Clarke County, I suppose.

S. How old was she at the time?

R. Oh, the license says 21, but I think she was 19. And she was the first one—the third girl but the first one to get married. That really ruffled my grandmother’s feathers. Because, you know, Myrtle was supposed to marry first. That was just the custom.

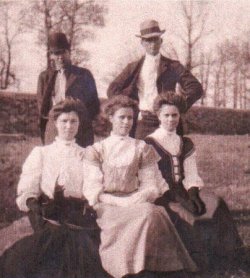

You see these ladies here? They are Aunt Myrtle, Aunt Hattie, and Mama [left to right]. They are ages 20, 18, and 16 (photo right). They all married men named “Will” Will Arnet, Will Ashby, and Will McCarty.

When you were 18, you got to wear a skirt and a blouse. Before that, you wore a jumper. But my grandmother hadn’t had a chance to make Hattie a skirt and blouse. So she’s 18 but still wearing a jumper.

I lost this sister in 1964, she was 50 when she died. And my brother was 70 when he died. And I’m still hanging around at – I’m 86.

S. So her sisters were Myrtle and …

R. Hattie. And then Mother. And there were two boys: Robert and Amny. Now there we get that Amny name again. But he spelled, or at least Mother spelled it, A-M-N-Y.

After they got married they lived on the mountain. They had saved enough to buy this place in Airmont in 1922. I think they paid $6,000 for it, for 104 acres to begin with.

Mother had children in 1910 (my sister Sadie) and 1913 (my sister Ollie). They were born on the mountain. And born at home. We all were born at home.

S. And then there’s you, and are there other children?

R. I had a brother Robert and in 1923 he was born. And then in 1924 he passed away. Just nine months old. And then in 1925, I came. Mother said I was the only baby that was planned. The others were “a Gift from God” is what she would say. I guess that’s the best way to put it. And then I had another brother, Kenneth, who was born in 1927.

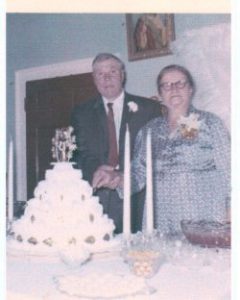

Now this photo is of their 50th Wedding anniversary, November 30, 1959.

Now this is what we all looked like when they’d been married 50 years (photo right — left to right: Kenneth, Roberta, Ollie, and Sadie).

This is Sadie, this is Ollie, this is me, and that’s my brother.

But we had a lot of good times. Now I’ve always thought when they bought this place they had to borrow $2,000 to stock it. Buy implements and whatever.

S. And a tractor?

R. Oh, good heavens, we never had a tractor. When they sold the place in 1959, he was still farming with horses.

You know how the Amish of today live. That’s exactly how we lived. No, we walked every place. We did get a car in 1930.

And my mother sold turkeys. Most of them, I think she sold dressed. Plucked and ready for the oven. Made a little bit more money than on the foot, you know. I know they had to be killed in a certain way.

I know she made $600 because she paid cash for the car. She paid for it, but my Daddy bought it. But you know, he always gave her credit. You know, Mama worked hard.

But I thought that was wonderful. To sell $600 worth of turkeys—$600 was a lot of money then. And let me tell you the way it had to be done. You didn’t go to the brooder and things like you do today. You had to watch the turkey and get the egg from the hen. They had nests.

S. You couldn’t trust the turkeys to raise their own chicks?

R. Heavens no. You had a place where they sat on these eggs. Now a chicken is 21 days. A turkey was 28 days. Now as long as you had the eggs under the turkey, she turned them every day, with her feet. But if you were saving a setting of eggs, which was 14, you had to turn them yourself.

Mother laid them in a box with corn meal in it. She put an X on the turkey egg. She’d flip that thing – go along and flip ‘em all. The next day she’d bring the X back up. he next day, turn it down. And they had to be turned every day. And then you’d put them under the hen, and she raised them.

They were in coops. Turned them out during the day. You’d chase after them and keep the hawks away. Most of the time we had guineas [hens]. They’re black and white, smaller than a chicken. And they have this squawky sound. They were just like a watchdog or something. There was a lot of hawks then, and they would come in and just pick these babies up. Of course, when the guineas would see them flying they would squawk, and it would scare the birds away.

S. And then, your mother sold eggs?

R. Oh yes. She sold hen eggs up till 1959. We had cows. Had 14 when I was a kid –and we sold cream. We had a machine called a separator. We separated the cream, and sold it. There was a place in Purcellville called Mountain View Creamery. They came around to get it once a week and they made butter. As far as I know butter was all they made. As long as we were at the farm we did these things—they were our money crops.

R. Oh yes. She sold hen eggs up till 1959. We had cows. Had 14 when I was a kid –and we sold cream. We had a machine called a separator. We separated the cream, and sold it. There was a place in Purcellville called Mountain View Creamery. They came around to get it once a week and they made butter. As far as I know butter was all they made. As long as we were at the farm we did these things—they were our money crops.

S. And your mother made butter too, and sold it to the boarding houses in Bluemont?

R. Well, I suppose you know about the train and how it came to Bluemont?

S. Yes. It came out from Round Hill in 1900.

R. Well there were a lot of places. You see, the people in Washington would come up here because it was cooler. They had to have a place to stay. They’d come up Friday and go back Sunday—something of that nature. Well, they stayed in these houses. My mother never took in any borders, but she made things for them. She made butter and pies and sold eggs and milk.

S. Do you remember where the places where people boarded?

R. Well, there was Mrs. Weadon [in Carrington House], you know, next to where Sonny and Betty [Colbert] and them live. And there was one, we went around on what do they call it now—Railroad Street – and then hook around and go up. This was before they built the by-pass [made Route 7 four lanes]. And their name was Simpson. Their house is no longer standing.

Artist Lucien Powell and Handyman Amos

Now if you go back to Airmont, there was a long driveway—McMichaels—they also took in guests. And Aunt Hatti’s place, named Airwell.

Before she bought it, Airwell was the place where the painter, Lucian Powell lived [American landscape artist, native Virginian, and Civil War veteran Lucien Whiting Powell, 1846–1930]. Aunt Hattie bought it from Mrs. [Nan] Powell in 1942. There were two families in there after Mr. Powell’s death and Mrs. Powell moved to Washington, Grimes, and Pomroy. Aunt Hattie and Uncle Will moved in about 1946.

You know how there’s two gates there. One above. At the upper gate, there was a house there that I remember, in the yard, in front of Airwell. Aunt Hattie and Uncle Will Ashby tore it down. I’d say that it had maybe six rooms upstairs, with numbers on the doors, and a big room on the first floor. It was two stories, painted gray, unfinished with wainscoting inside.

Downstairs is where they danced. On Friday night or Saturday night. Somebody came by and played the fiddle and they danced to that. The guests would rent the rooms from the Powells. They would take meals in the Airwell’s dining room. It was a big long room. And that was also where Mr. Powell painted.

S. About when was this?

R. This was in my lifetime. I can remember when Mr. Powell got a car. Of course, later, Papa used to drive Mr. Powell around, and Sam McMichaels also drove him. What I remember is that he would take Mrs. Powell to the store, maybe on Friday. He sat around dressed up. He wore a suit—he never dug a ditch. He just sat around and painted—very good painter by the way.

What he would do? Back then they would use those old horns—“oooga, oooga”—you’ve heard them in old movies. Well, he had one of those. Now when they went to the store, he had to just get up, get dressed, and blow the horn. She had to take care of the chickens, the cows, and other stuff to fool with.

Mama would say, “Why don’t he stop that?” Poor Mrs. Powell was just run to death.

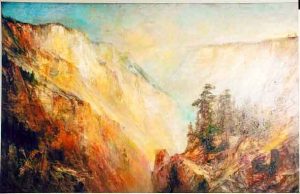

He was a very good painter. One of his paintings is in the Geological Survey, there in the lobby – the picture of the Grand Canyon. [On loan from the Smithsonian.]

S. I’ve heard that he did his painting in that little cottage by the road.

R. I don’t know how that tale got started, but I’ll tell you who that cottage was used by. He was a handyman, his name was Amos. He was black. He did all the yard work.

The Powells went to Washington every winter.

Mr. Powell died when I was still a little girl. But Mrs. Powell lived until I got out of high school, in 1942. They sold the place to Aunt Hattie. Well, the old house was falling down. It just didn’t get any upkeep, but Aunt Hattie and Uncle Will fixed it up.

Amos died. And I can remember, he died there at the Powells. And they carried his casket, I guess it was a pine box, I don’t know. And they carried it across the place where whoever put those duplexes. Six men. I don’t know if they were black or white. I just don’t remember that. But I remember when they started up there, carried it from the Powells, in their hands. And he was put in the Powell lot—they had their own burying ground. It’s still up there now, just full of briars.

He died in the caretaker’s house, I don’t know how, when, or why. I remember him dying and I remember them carrying that casket. It was quite a sight for a child. I had never seen a casket.

We went up there. I remember they had the service, I remember singing. And the neighbors all came around. Everybody walked. No cars then. There wasn’t any truck to take the body up there. I don’t know how they would have gotten in there with a truck—unless they go on “Mrs. Mac”—Mrs. McMichals—and come in that way.

Telling Time by the Train Whistle

S. Tell me about the train when you went to school in Bluemont.

R. See it came from Round Hill, across the road (Route 7). Before it got there it blew the whistle. And then we knew whatever we were doing, if we were playing, to get ready because we had to form lines at the back there.

R. See it came from Round Hill, across the road (Route 7). Before it got there it blew the whistle. And then we knew whatever we were doing, if we were playing, to get ready because we had to form lines at the back there.

And we’d have the Sousa marches—we had three or four records of the John Philip Sousa music. And we marched. It was usually in 3/4 time. He teacher would tell us, “Now this is in ¾ time.” And she take two fingers and show us the beat. She’d have us all doing the time. And that’s how we marched in, and that’s how we learned the time. And I thought that was interesting.

S. Who was the teacher when you went to school?

R. Well, Miss Lunceford, she was the principal. I can’t say enough good things about her. I wish every school in America had Eliza Lunceford. I tell you one thing, you wouldn’t have what you have today. ‘Cause she’d crack your butt—it didn’t make a bit of difference in the world if you were a six-foot dude or a big man. She’d talk to these great big boys, didn’t have to do anything, “Do you want me to use my muscle on you, you’d better straighten up. You want me to write a note and you take it home to your mother today?”

S. Now explain to me again. The train sounded the whistle and then—you knew it was a certain time of day?

R. We’d be playing ball, say. Before school; the bus had already gone. And we had to get in line. It was three classrooms. And stood there like little soldiers, there wasn’t no pushing and shoving. And then she’d come out. First grade through the seventh. Oh, we liked it.

S. Then when did the train stop coming?

R. It stopped coming in 1938. And I know that to be exact, because that was my last year at Bluemont and my first entry into high school. As long as I went to Bluemont School there was a train.

S. You know, some people say 1930, some people give other dates. But now I know I have it from the horse’s mouth.

R. That is an exact date. There’s a lot of controversy about when did the school stop. When did they close our school down? It was 1962.

S. I guess you didn’t have hot lunches like schools today.

R. Now we did get that. We did get the lunches. Not when I went to school. We carried a little bag lunch. Once in a blue moon, they’d make a pot of soup. I don’t know, I guess the teachers just did it. Oh, that was good. You could smell it when you went in, and oh, it smelled so good.

S. Would the teachers bring the ingredients or the students?

R. Yes. The students. And the same way with milk. The kids brought it from home. They’d make cocoa sometimes. Now you just pour some chocolate in some milk, but then they had to start from scratch with the cocoa and the sugar and all. So they’d make it, and it was such a wonderful thing. The teacher knew that we had food. We didn’t have a whole lot of it, but we had food.

We wore feed sack dresses.

S. You mean the girls wore dresses made out of sacks?

R. Feedbags. See, my mother made all my clothes, my mother could sew too. And if something should happen, you know you could always get by.

And even after I married, I was that long away from the grocery store and you go and you just don’t have this or that. You plan something and you go to the cupboard and it’s not there. What did you do? Why, you substituted. You didn’t just throw your hands in the air and say, “Well, no supper in this house tonight!” There was just so many things.

Roberta Underwood Part 2: The War Years